Physical Address

Kigali, Rwanda

Gasabo, Kimironko

Physical Address

Kigali, Rwanda

Gasabo, Kimironko

Africa has been experiencing the fastest urbanization recorded with an average annual urban growth rate of 3.5% in the last 20 years, but what does that mean for us in the construction industry?

This rapid growth is resulting in African cities expanding faster than ever, and this is coming at the expense of the continent’s ecological system.

We know we can’t escape urbanization, but we can rethink how we design and inhabit our cities in ways that can protect our environment.

Today, I want to talk about a concept that I find not only interesting as an architect, but also see it as a longterm solution that can take our cities from destruction to regeneration.

Landscape urbanism in simple terms can be described as the idea of designing cities through their ecological system instead of through their buildings.

It basically brings two things that usually are manipulated to work against each to now work together for the better: nature and the built environment.

If we want to build cities that are truly resilient and reflective of the unique African contexts, we need to adopt this type of thinking, not just as African architects and urban planners, but as the public too, because we have established the importance of the public.

In order to design cities that will flourish in the long run, we need to understand the context in which we are designing.

In essence, context-specific design is all about developing solutions that are tailored to fit a given environment and the people within said environment.

When you look closely at different cities around the world, there is always at least one site that carries a certain meaning or memories.

This is as true for the Eiffel Tower in Paris-France as it is for the Pyramids of Giza in Giza-Egypt, for example. These places can also be ecological, like the Nyungwe National Forest in Rwanda, etc.

And this is where landscape urbanism comes into play–by responding to the memories and meanings carried by these spaces to treat nature as infrastructure.

Nature infrastructure includes using wetlands as natural water filtration systems, vegetation for airflow and cooling systems, agricultural landscapes for limiting flooding impacts, topography as guides for settlement patterns, and so many more.

Nyandungu Eco-Tourism Park in Kigali, Rwanda, is a good example of how wetland rehabilitation promotes both sustainability and resilience through working with nature instead of against it.

The wetland was badly degraded by human activities before REMA launched its restoration in 2016 in an effort to show how urban wetlands are helpful in fighting pollution and flooding.

This example shows how context-specific strategies can take Africa’s urban development from destructive–to the environment–to regenerative.

Context-specific design can also look as simple as designing to accommodate human behaviours and needs.

Think designing proper paths in a place that had an informal shortcut. Or providing natural shading along sidewalks. Or providing usable public water fountains. Or adding public benches in green buffer zones.

The African built environment goes beyond ecological landscapes and concrete buildings, it also has cultural essence.

In many African histories, you will find important stories, traditions, rituals or myths that are associated with specific places.

These histories connect the people to their lands, yet modern urban planning often overlooks this living heritage.

When you look at the Rwandan traditional houses, their circular shapes were a meticulous and intentional design decision that was influenced by their culture of community and the environmental landscape.

Even the materials choices and structures choices had reasons behind them.

We should not lose sight of these traditional values and cultures because learning from the past doesn’t necessarily mean we are romanticizing it, it just means we can learn from its wisdom with what worked then that can be incorporated into modern designs.

Founding sustainable landscapes on culture isn’t just about borrowing from the past, though.

Culture is what gives us our unique identities, and allows us to express ourselves in our individuality and communities.

Our spaces should be designed to allow room for that without disrupting the ecological system.

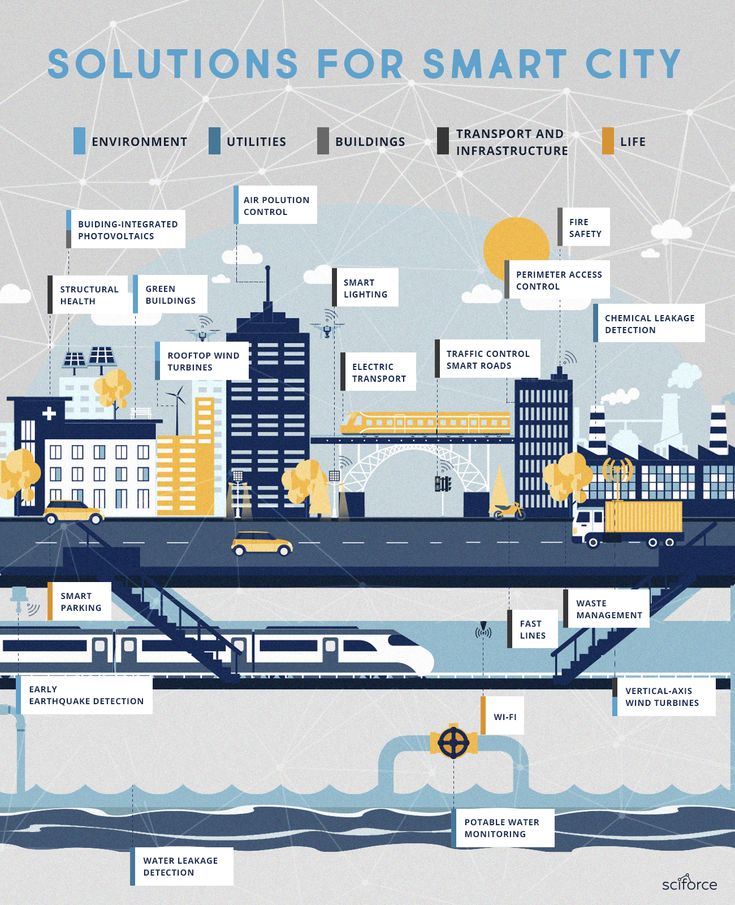

We are moving in a fast-paced world where technology is always evolving and if we don’t regulate it to go hand in hand with ecology, we risk destroying our environment further.

Today, thanks to the use of GIS mapping, and the likes of such tech, architecture has soared higher than ever before, not just in planning but also in designing and translating in the daily use of spaces.

The good news is that tech offers so many opportunities for reimagining urban landscapes and infrastructure.

With tools like smart sensors available to use in designs, we can reduce energy usage and wastage among others, and with adequate facilities we can go green with renewable energy systems.

The opportunities are endless, yes, but the question remains: how do we adapt and localize these technologies to fit each unique context in a way that does not disrupt our ecology?

This means that there are design decisions that should be made way before we even conceptualize the designs themselves.

Let me take you back to the Nyandungu Eco Tourism Park for a moment.

This park that used to be a degraded wetland is now an ecosystem that not only filters water and restores biodiversity,but also offers relaxation and recreation for both locals and tourists

That is the outcome we are looking for! Spaces that can be transformative and regenerative.

Resilience is both environmental and social. Understanding that is the first step in creating spaces that can withstand the test of time.

Our designs should not just celebrate the environment and the community, they should protect these ecosystems while also improving the lives of the people who live in, work in, or even just visit them.

This can look like planting trees that can help the land on which they are planted while giving fruits for the people on that land for example.

I also believe that resilient architecture is one that can live with nature without succumbing to it. Think of the lianas that grow climbing on walls. These walls that welcome them are resilient to me.

As Africa undergoes urbanization, we have the rare opportunity to shape how our cities will look in the future.

I see landscape urbanism being one way that the construction industry can use to contribute in making sure that this urbanization does not destroy us or our environment.

If we learn to work with nature and not against it, we will end up with cities that breathe life and that can sustain our own for generations to come.

Let me know what your thoughts are on taking this transformative approach, and what other alternatives you see being on parr or even better!

This read was a blog rendition of an essay competition that I participated in recently, but I thought the prompt was so interesting so I thought I’d make it blog-friendly. I hope you enjoyed these thoughts today. See ya soon!