Physical Address

Kigali, Rwanda

Gasabo, Kimironko

Physical Address

Kigali, Rwanda

Gasabo, Kimironko

A while back when I started this blog, I talked about what makes a public space truly work and one of the points I touched was inclusivity.

We live in a very diverse world, where all of us have different needs. Some more than others. But that doesn’t make any one of us less deserving of accessing basic infrastructure with ease.

Inclusive design is an empathetic approach to making spaces welcoming to everyone, catering to everyone’s needs.

Today I want to take you through some key features/principles of this design philosophy, and a few case studies of projects that have tried to implement it.

Before writing this blog, I had a less evolved understanding of the concept of inclusive design than I do now.

True, I had encountered the idea multiple times, especially in different studios as we were always encouraged to think of making sure our designs were accessible for all.

But the thing is, when you mention accessibility to an architect it leaves room for the most common interpretation: accessibility in the literal sense i.e. how will people enter my project if they have wheelchairs (to which the answer is usually adding a ramp and elevators where applicable).

Then, when you go further the professors ask you to also think about other disabilities.

And you usually think just because your project has a ramp, elevators, brailled walkways and signage, and if you’re really “thoughtful, a well designed acoustic system, then you have achieved inclusivity.

It wasn’t until I started working on a playground project in Rwampara, Kigali, that I started seeing how inclusivity goes beyond catering to special needs and calling it a day.

In fact that is just the first step–and a very important one too, don’t get me wrong.

But as I went on site visits, talking to girls around the community looking for their interests when it comes to playing and entertainment, I realized that most of them were not indifferent as it had first looked like.

When I took the time to just talk to them, not in a probing interview way, I found that most of them loved traditional dancing and singing, but they could only have the chance to access facilities that encouraged them to do that at school.

Their community, Rwampara, has no abundance of formal spaces for the community to express themselves through sports and creativity, and much less for girls and women.

Women in the community will just create spaces in front of their houses/in gardens where they can sit and talk.

But the younger girls who want more rigorous activities are marginalized by the lack of proper resources for them.

And when you look further, you see that there are gaps when it comes to age in many of our public spaces, and even in spaces accessible to the public in general.

It’s rare to find a restaurant that has a space dedicated to kids, and although I can agree not every place has to have them, it’s an aspect most places should consider while planning their programmes.

A few days ago, I passed by the Kacyiru bus stop area, and I was pleasantly surprised by its design. The aesthetics were nice and all, but what really made my heart happy was seeing the little room dedicated to mothers and their babies.

It is heartwarming seeing how we are starting to adopt a more inclusive approach when it comes to designing publicly accessible spaces, but I do think we still have a long way to go, and it is our responsibility to adopt it in the first place.

If I had to define inclusive design in short, I’d say it is a design approach in which we create spaces that are accessible, safe, welcoming, and usable for as many people as possible, by keeping different needs in mind from the very beginning of the design process.

I think I have covered most of the basic stuff above, but I want to give you the main things to keep in mind as you design inclusive spaces. Consider these key inclusive design principles in a way.

Inclusive architecture starts with the idea that everyone deserves to enter, move, and experience a space in the same way.

This means avoiding separate or secondary solutions and instead creating features that work for all users from the start.

People interact with buildings differently depending on age, physical ability, or even daily circumstances.

Good inclusive design allows for these differences by offering options (like adjustable elements, movable furniture, or multiple circulation paths) so the space adapts to people, not the other way around.

Spaces should make sense as soon as you enter them.

This can be done by having clear layouts, logical transitions between areas, and intuitive wayfinding as a way to help everyone navigate comfortably, especially in public or unfamiliar environments.

Not everyone perceives information the same way. Using a combination of visual cues, tactile markers, contrast, lighting, and sound ensures that directions and spatial cues reach people with different sensory abilities.

A well-designed project should not exhaust its users.

We should focus on minimizing unnecessary physical force exertion by designing gentle gradients, smooth transitions, easily operable doors, and comfortable distances between key spaces.

Different bodies and mobility tools require different amounts of space.

Providing generous circulation and turning spaces, and seating options ensures that everyone–from wheelchair users to parents with strollers–can move freely and comfortably.

People make mistakes and design should anticipate this.

By minimizing hazards and creating safe circulation and transition zones, architects reduce the chances of accidents and allow users to feel more confident moving through a space.

Architecture shapes social interactions and should acknowledge cultural diversity, and this is something I keep emphasizing on this blog.

What I essentially mean here is creating spaces where people from different backgrounds feel welcome, represented, belonging, and comfortable, instead of designing from a single cultural viewpoint.

People experience space through more than just sight. We have to pay attention to acoustics, textures, temperature, and lighting if we want to create environments that feel calm, balanced, and supportive, especially for users who are sensitive to noise or visual clutter.

The most inclusive spaces come from involving the actual users in the design process. I will probably talk about a community-centered approach in design in the future more deeply, so stay tuned.

But basically, listening to different groups like older adults, people with disabilities, children and vulnerable community members helps architects understand needs they might otherwise overlook.

Now that we have looked at the core principles of inclusive design, let’s look at some examples of projects that embody inclusive design.

This building is designed entirely around accessibility and equality.

Circulation is seamless, with ramps, wide corridors, and intuitive wayfinding that allow people with different mobility needs to navigate independently.

The layout removes physical and social barriers, and materials, lighting, and acoustics are carefully chosen to support users with sensory sensitivities.

The project shows how a workspace can empower people with disabilities rather than simply accommodate them.

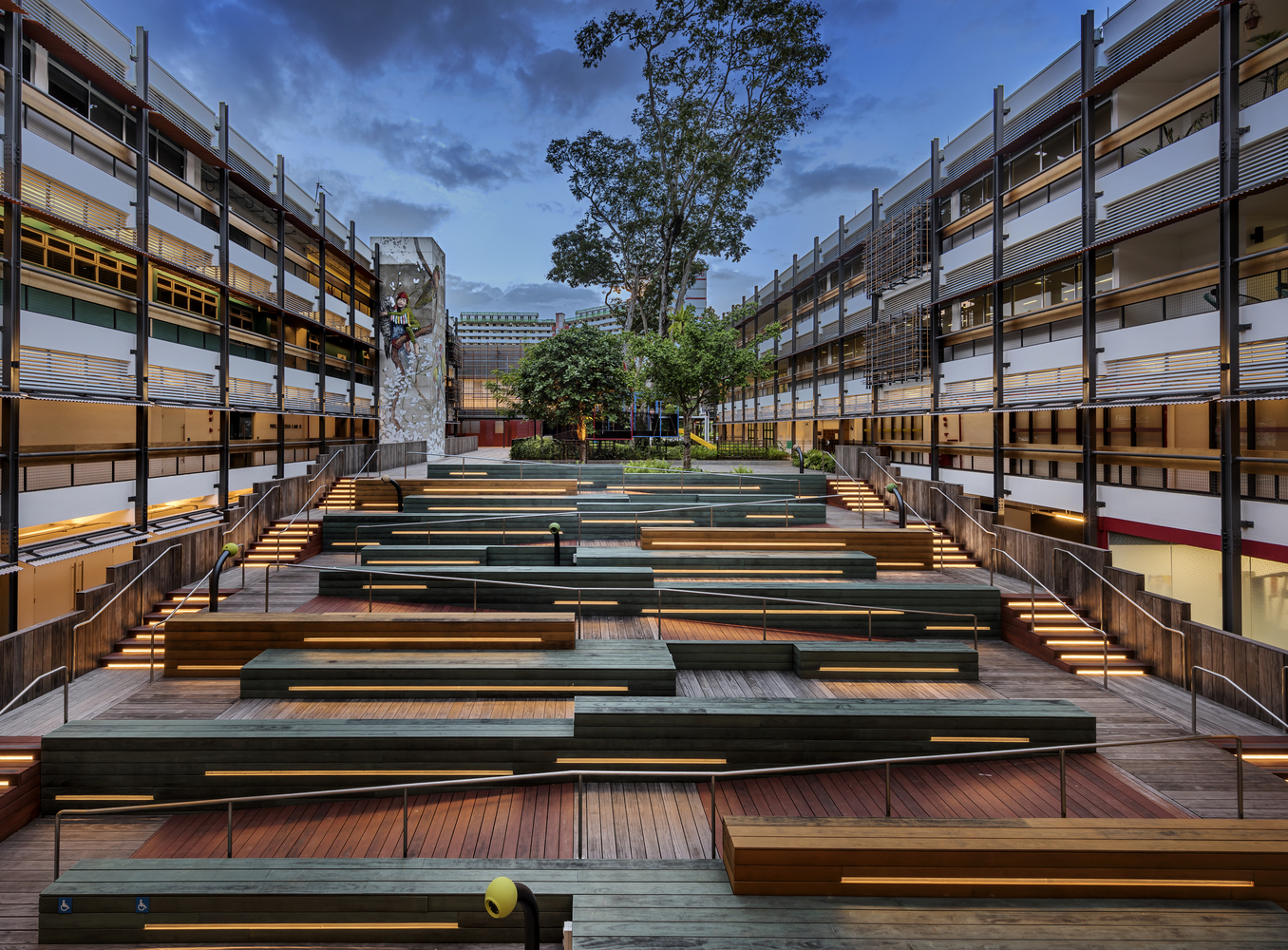

Enabling Village transforms an old school campus into a community hub fully centered on inclusivity.

It blends universal design with social programming, offering accessible paths, tactile cues, step-free connections, and legible layouts that support users with mobility, visual, or cognitive challenges.

The architecture is welcoming, and human-centered, showing how adaptive reuse can create inclusive public spaces that feel open to everyone.

The High Line is a major example of inclusive urban design. The elevated park integrates step-free access through elevators and gentle ramps, making a once-inaccessible industrial rail line usable for millions of people.

The wide pathways, seating variety, shade, and sensory-rich planting create a public space that accommodates diverse users, from older adults to children and people with mobility challenges.

It really shows how cities can reuse infrastructure in ways that welcome everyone.

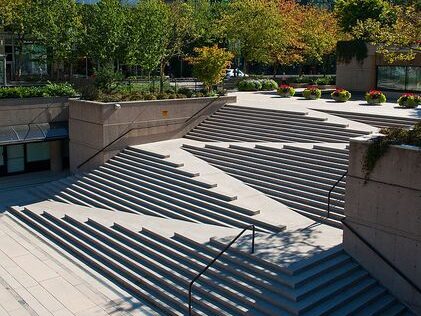

This project focuses on creating an open, community-friendly park with features that support usability for all ages and abilities.

The design includes barrier-free circulation, generous green spaces, shaded seating, and activity zones that encourage social interaction across different demographic groups.

Paths are clear and accessible, and the layout promotes safety, and a sense of belonging. The park illustrates how inclusive design at an urban scale can strengthen community life.

Designing with empathy and creating spaces for every need imaginable is not a burden, it is a responsibility and a good way to ensure that spaces can be used comfortably and enhance the user experience.

Like I said last time, when you design for the most vulnerable people of a community, you are designing a better experience for all.

I hope you walk away with a mindset to design spaces that can be accessible to everyone regardless of their age, gender, religion, disabilities, etc.

I had a great pleasure writing this, and I’m hoping it was as much of a good read for you! See you very soon, and if you don’t follow me head over to my socials, and be on the lookout because I have something special coming up real soon!